‘SPUDS FOR THE PRODS’

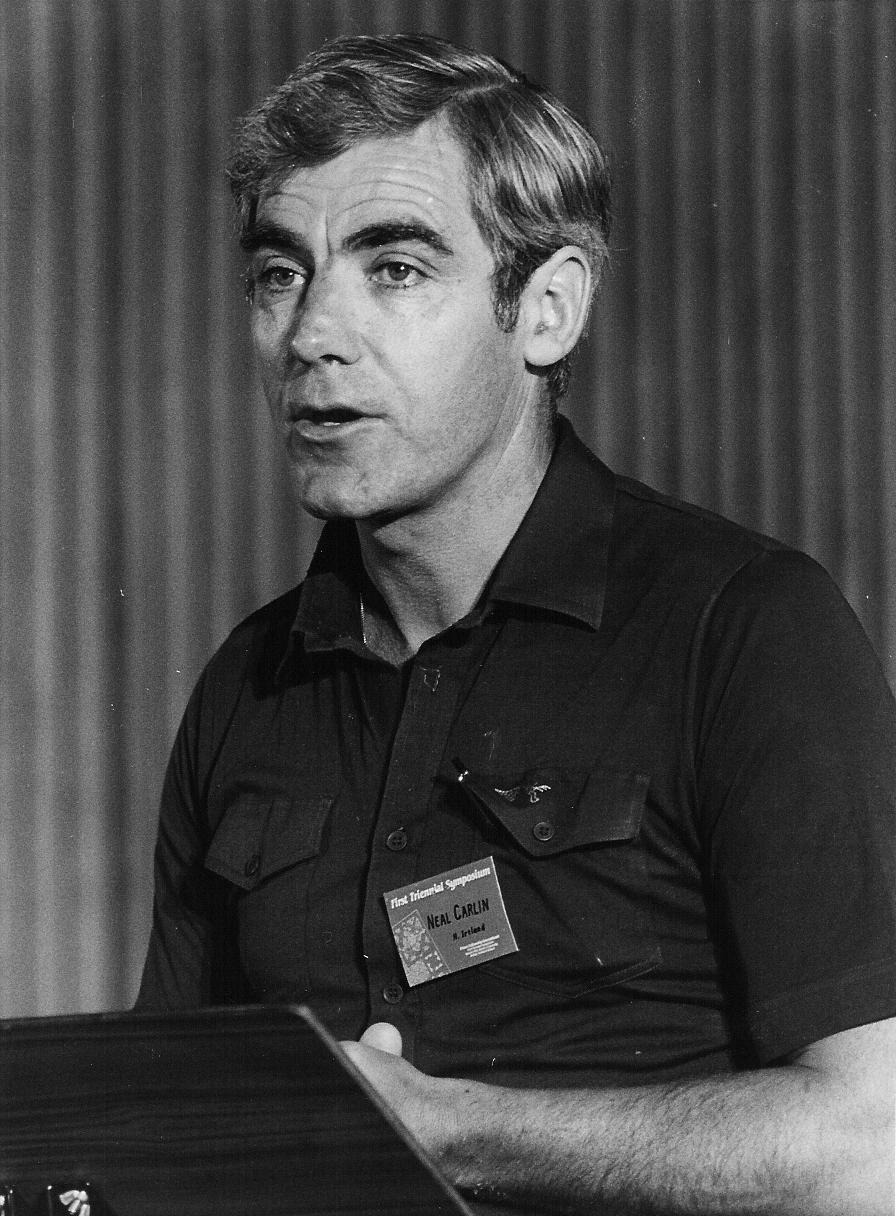

‘A Personal Testimony’ REV. NEAL CARLIN

Neal was one of the first pioneers of renewal in the Catholic Church in the early 1970s. He set up areconciliation ministry in Columba House in Derry in what was a bombed out RUC station.

I was born in Derry, in Ballyowen House, a large house out in the country. My great-grandfather was a very rich man, owner of many properties, including a wholesale Wine & Spirit Merchants business in Derry’s Waterside. I have a relic of those days on the mantelpiece, an old crockery bottle embossed with the words ‘Neal Carlin & Company 1840’. We found it, about three feet down, when a digger was digging up the yard outside the retreat centre established by Columba House in Dundrean, Co. Donegal. My great-grandfather employed a housekeeper from Donegal whose practice it was to lace the children’s milk with whiskey to put them to sleep. This had a tragic outcome, in that both sons became alcoholics at a very early age, one dying at the age of eighteen and the other, my grandfather, dying at the age of thirty-three.

We moved from Ballyowen House into the city, partly to escape from the constant, harassing visits to our house by the RUC. That was back in 1940—42, during the war. My father was known for his nationalist views, and for being the sponsor of ‘The Neal Carlin Cup’ for Gaelic football. He found himself the target of attention from the police. My mother often talked of the RUC banging at the door at two or three o’clock in the morning, ‘checking up on Republicans’. She would have to get up and make them tea. If they weren’t given tea, they would return two or three times that week. If they were treated to the hospitality they demanded, they might not return until the following week. Nobody could do a thing about it. It was frustrating and demeaning for my father and others subjected to like treatment. Such behaviour formed part of the build-up to what was to erupt many years later in the rebellion following the civil rights campaign.

There were ten of us altogether in the family. We lived for a couple of years in Derry and then moved eleven miles away to Newtowncunningham, in the Republic of Ireland. It was a village associated with another village up the road, called Manorcunningham. Old man Cunningham had come across as one of the Planters from Scotland. They settled in what was the best land in this part of Donegal. There was a hot debate, around the time of partition, as to whether Donegal should be divided, with the eastern section being included in the new entity of Northern Ireland. All I recall is the great number of Presbyterian and Church of Ireland farmers — they owned all the land around that way. We had special school holidays for gathering the potatoes. We got three weeks off from our little three-room school every October, to gather spuds for the ‘prods’ (a shortened version of ‘prodesans’, as Protestants were colloquially called).

Anyway, I went to an all-Irish boarding college. All that was Gaelic was reinforced in me. For example, we were punished with a strap if we were caught playing soccer in the school grounds. I played Gaelic football for Donegal and did a lot of running. I got the surprise of my life in college when I won the mile race. I was sixteen and in my third year. In fourth and fifth year I won it again and then, all through the seminary, I won the cross-country and the mile. I love running. But today I’m ‘coopered’, as they say, with a sore foot, which is why I’m slimming these days. I need to lose weight.

It was 1958 when I left secondary school and entered the seminary. I had some difficult times there, finding it such a rigid system, with little room for compassion. I was ordained in 1964 and went to Scotland. I was still very involved with football and athletics. I was president of the Gaelic Athletic Association in Scotland for two years. I studied for a teaching qualification and began to teach religion in St Margaret’s High School, Airdrie, in 1972. I was very friendly with ministers of different denominations. And then suddenly it happened - Bloody Sunday. Six of my brothers had been on the March on Bloody Sunday and they all gave me their reports. I felt helpless. Deep down memories of past injustices surfaced. I felt the Church was standing back and doing nothing. I felt passionately for my people at home, but didn’t know what I could do to help. In those days, a lot of my friends were leaving the priesthood for various reasons and I began to agonise over whether I should stay or not. The upshot of all this turmoil was that I fell into a kind of a depression, which lasted for about six months.

Then I was moved to another parish. An old priest, John Cosgrove, rang me and asked if I would go to a prayer meeting in the house of a friend of his up in Stirling. As a courtesy to him I went. His friend, a recovering alcoholic, had a fourteen-year-old daughter who was suffering from leukaemia. There were just the four of us there: an old retired priest, a recovering alcoholic, a girl with leukaemia and a depressed curate. Quite a set up! They passed round some song sheets and the three of them started singing. As they sang the song ‘Spirit of the living God fall afresh on me’, I began to get an inner peace. I found myself sitting there smiling. I was experiencing the anointing and blessing of God. It was the beginning of something new.

An elder in the local Church of Scotland, gave me a book, Nine o’Clock in the Morning by Dennis Bennett. I read there about forgiveness, about the reality of the power of Jesus Christ, about the Lord being alive in our hearts, about the power of the Spirit and His gifts that enable us to prophesy, to teach, to heal. I had heard about these things before, but here for the first time I was reading about somebody who had actually experienced the reality of them. I was very excited about that. It engendered in me a new hope. It was like coming alive again, being renewed in my spirit. I became more at peace with myself and with others. I told my Bishop that I now felt able to go back to work in Ireland.

I was given a temporary post in the Cathedral in Derry. For me now, the answer to the Troubles lay in the work of reconciliation, in preaching and teaching Christ as the only one who could overcome evil arid violence. A prayer meeting was started in the Northlands Rehabilitation Centre for alcoholics and drug addicts. I was astounded at the power of God released in those gatherings. People were healed in mind and body. Miraculous things happened in abundance.

There is a non-residential community of fifty-eight full-time members attached to Columba House. We meet for prayer every Wednesday night and are committed to a range of caring activities in the local community. We are currently exploring, with the support of ministers from other denominations, the possibility of establishing a centre for the care of alcoholics and drug addicts. The centre would be located on a farm and I would see it very much as being a centre for spiritual renewal, with an integrated programme of prayer and physical work forming part of the healing process. I would greatly appreciate readers’ prayers for the Lord’s blessing and provision for this new project, the White Oaks Centre, Derryvane, Muff, Co. Donegal. It will be an interdenominational centre on the border between North and South, aiming to draw Christians together from different cultural and denominational backgrounds to join forces in caring for those suffering from the abuse of alcohol and drugs.

We organised large conferences. Then, suddenly, I was asked to leave the Cathedral. To this day, I don’t really know why. The Bishop in Scotland was very surprised and annoyed. He asked for an explanation, but wasn’t given it.

That was a very painful time of rejection. I had considered myself married to the church. That was a very painful time of rejection. I had considered myself married to the Church, but now felt betrayed. It actually became a physical pain in my stomach. In time, the Lord healed me, but it took a long time; for me, forgiveness came gradually, in layers. But God had a hand in it all — as Joseph said to his brothers, ‘What you meant for evil, God meant for good.’ Had I not been set aside in this way, Columba House for Prayer and Reconciliation would never have been established in Derry, nor would St Anthony’s Retreat Centre in Dundrean, Donegal.

I got permission from my Bishop in Scotland to spend six months in America— visiting various houses of prayer. On arrival, the airport chaplain put me up for the night. In my room there was a board with an inscription on it that riveted my attention: ‘They that wait on the Lord shall renew their strength, they shall mount up with wings as eagles; they will run and not grow weary, walk and not faint’. It was Isaiah 40 verse 31. A short time before, I had gone on retreat to Nunraw Abbey, a Cistercian monastery in Scotland. While there, I had received a clear impression of a large eagle in flight and a strong sense that I was to wait on God. I had said to a friend of mine, ‘You know the Bible. Is there anything in it about waiting and an eagle?’ He couldn’t find any thing. Now here it was in front of my eyes. I remember taking the piece of board outside and telling the first people I met how I had come 6,000 miles to get this text!

About a week later I was in San Diego and I went to a large prayer meeting, of about 800 people. A man stood up and said ‘I have had a scripture given to me three times this week, and I know it’s for someone here.’ I instinctively knew that Isaiah 40 verse 31 was the scripture he was going to read. And he did. Some months later, I was in a House of Prayer in New Jersey, with a Fr. Brennan. I told him this story, and he threw open the door of his room. There on the wall was a big painting of an eagle with the text of Isaiah 40 verse 31 on it. He gave it to me to bring home with me.

When I came back to Ireland, in October 1979, Cardinal O’Fiach arranged for me to work as a kind of freelance chaplain in the prisons. I had an appointment with him one day to discuss my future and stopped in Craigavon on my way to see him. I asked a man who was out walking his dog if he knew where I could get a cup of tea. And he said, ‘You can come to my house, sir.’ He joked with me over tea about me, being a priest, having tea in a Protestant house in a Loyalist area. There was a book of Scripture readings lying on the table and I casually flicked it open. There facing me was Isaiah 40 verse 31. I sensed the Lord speaking to me very clearly, ‘The cardinal is a good man, but I told you to wait on Me.’ So when the cardinal offered me an appointment in his diocese, I said, ‘If you don’t mind, I really feel the need to wait and see what’s going to happen.’ And ultimately, after a long wait and much prayer, the answer came. I was sitting in Bethany House down in Wexford with Norman and Jean Ruddock, a Church of Ireland minister and his wife, and Fr. Staples, who had been my spiritual director in the seminary. After praying in tongues, there was a great silence, a great sense of God’s presence. These words came clearly into my mind: ‘In a few days you’ll meet a stranger who’ll point out to you a house.’ That was exciting.

At that time, I was working one day a week in the Northlands Centre in Derry. That week, a man whom I’d never met before came up to me during coffee break and said, ‘Father Neal, what you need is a large house. I know where you can get one.’ He brought me down to Queen Street, to a bombed-out site, four storeys of rubble. And I knew, I just knew that that was it. I had £200 in my pocket, a broken-down old car and no income. I didn’t know how it was going to come about, but I knew it was right. I woke up one morning with a person’s name in my mind, a local builder. I went straight to him. He said, ‘I don’t have a lot of time, what is it?’ I said, ‘Two sentences. There’s an old house in Queen Street. You buy it and I’ll live in it.’ He looked at me for about three seconds and said, ‘OK.’ It was as simple as that.

The building had almost been restored when the builder suddenly went bankrupt. He told me, ‘I’m going to have to sell the house in a couple of weeks to some body who’ll give me a good price, unless you can come up with the money.’ Then the pressure was on. We needed £30,000. The name came into my mind of someone I had met for about ten minutes at a retreat in Dublin. I somehow knew that if I drove to Dublin I’d see him at seven o’clock that night. So I went, and phoned for an appointment. His secretary said it was impossible, as he had a meeting scheduled with his accountant, who was flying in. from London. I said, ‘He’ll meet me at seven o’clock tonight. I’m sure of it.’ She rang at six and said, ‘I don’t know what has happened, but the meeting with the accountant has been cancelled. He wants you to come up here for dinner at seven.’ I walked out of there two hours later with a plastic bag with £10,000 in it.

I thought to myself on the way home, ‘I am either the greatest conman alive, or the Holy Spirit is at work!’ And I knew the latter had to be true, because that guy was a shrewd businessman, yet he handed me ten thou sand quid with no strings attached. The rest of the money came in just as dramatically. An old colleague of ‘mine from Letterkenny, a retired psychiatrist, came to visit. One of the volunteer workers happened to mention to him that we were short of cash. My friend came to me and said, ‘Would you be embarrassed if I gave you £20,000 free of interest for as long as you need it?’ Apparently he had recently received precisely that sum, on his retirement. He had prayed about what to do with it, and felt the Lord wanted him to use it for some good purpose. So he put his retirement cheque in an envelope on top of his wardrobe and waited. And that is how the Lord provided for the building of what became Columba House, a centre for prayer and reconciliation. So I don’t have to be told that the Lord is good and that He’ll stick by you if you stick by Him.

Meanwhile I continued with my work in the prisons. We started two prayer and Bible study meetings in the H Blocks in Long Kesh, involving thirty to forty men. There was some concern among the Republican leadership when they learned that men were being converted to the Lord and turning away from Republicanism. I have letters from a lot of those men, saying how much they were blessed by those prayer meetings. Later, many of those prisoners were transferred to Magilligan Prison in Derry, where we attempted to start an interdenominational prayer meeting. I knew that some of the Catholic prisoners would have come to the prayer meeting but were not yet at the point where they could cross the Catholic/Protestant divide. I suggested that maybe we could facilitate these people and help further the reconciliation process by having two united prayer meetings per month and two meetings where Protestants and Catholics would meet separately. The next day, the Governor telephoned me and accused me of trying to undermine the integrationist policy of the prison. He told me I would no longer be allowed into the prison. When I tried to gain admittance, I discovered a red card in the pigeon hole allocated to me, barring me from all future admission.

Pressure had also been building from another Christian ministry at work in the prison, which seemed to have difficulties in really respecting the fact that Catholics could be Christians. The situation was com pounded by the fact that a few of the. Catholics who participated in the prayer meetings ended up being proselytised by members of fundamentalist, anti-Catholic denominations. I later learned that the Bishop held me responsible for this and told the prison chaplain not to invite me into the prison any more. I got the boot from both secular and Church authorities.

Looking back on that time of prison ministry, I can see how all the cracks in the Body were exposed and old fears, old prejudices, old hates, old long-standing notions of each other emerged. There ‘has to be an immense conversion in the heart of Protestants in our country. A paradigm shift is needed in the Protestant psyche, if they’re going to love Catholics as Christians and even more so a Roman Catholic priest. I mean, whatever chance the ordinary Catholic has of being a Christian — how could a priest be a Christian? I praise God for those Protestant ministers who can openly embrace me as a brother. I sense the warmth of complete acceptance when it is there and am pained by the coldness of its absence. No amount of nice words and no amount of pleasantries can disguise the absence of brotherly recognition.

There is a non-residential community of tewnty-eight full-time members attached to Columba House. We meet for prayer every Wednesday night and are committed to a range of caring activities in the local community. We are currently exploring, with the support of ministers from other denominations, the possibility of establishing a centre for the care of alcoholics and drug addicts. The centre would be located on a farm and I would see it very much as being a centre for spiritual renewal, with an integrated programme of prayer and physical work forming part of the healing process. I would greatly appreciate readers’ prayers for the Lord’s blessing and provision for this new project, the White Oaks Centre, Derryvane, Muff, Co. Donegal. It will be an interdenominational centre on the border between North and South, aiming to draw Christians together from different cultural and denominational backgrounds to join forces in caring for those suffering from the abuse of alcohol and drugs.